In 1935, after years of working for Martin and Consolidated aircraft companies, Lawrence Dale Bell founded one of his own, the Bell Aircraft Corporation. Two years later a prototype of the company’s first military aircraft, the Bell Model 1, also designated YFM-1 Airacuda, was ready to fly. It was a heavy interceptor-fighter, a bomber destroyer, whose design was in many ways a radical departure from mainstream approaches of the time. It featured a number of design solutions that had never been used in aircraft industry before. Some of them were never used in any aircraft after Airacuda either.

Powering the plane

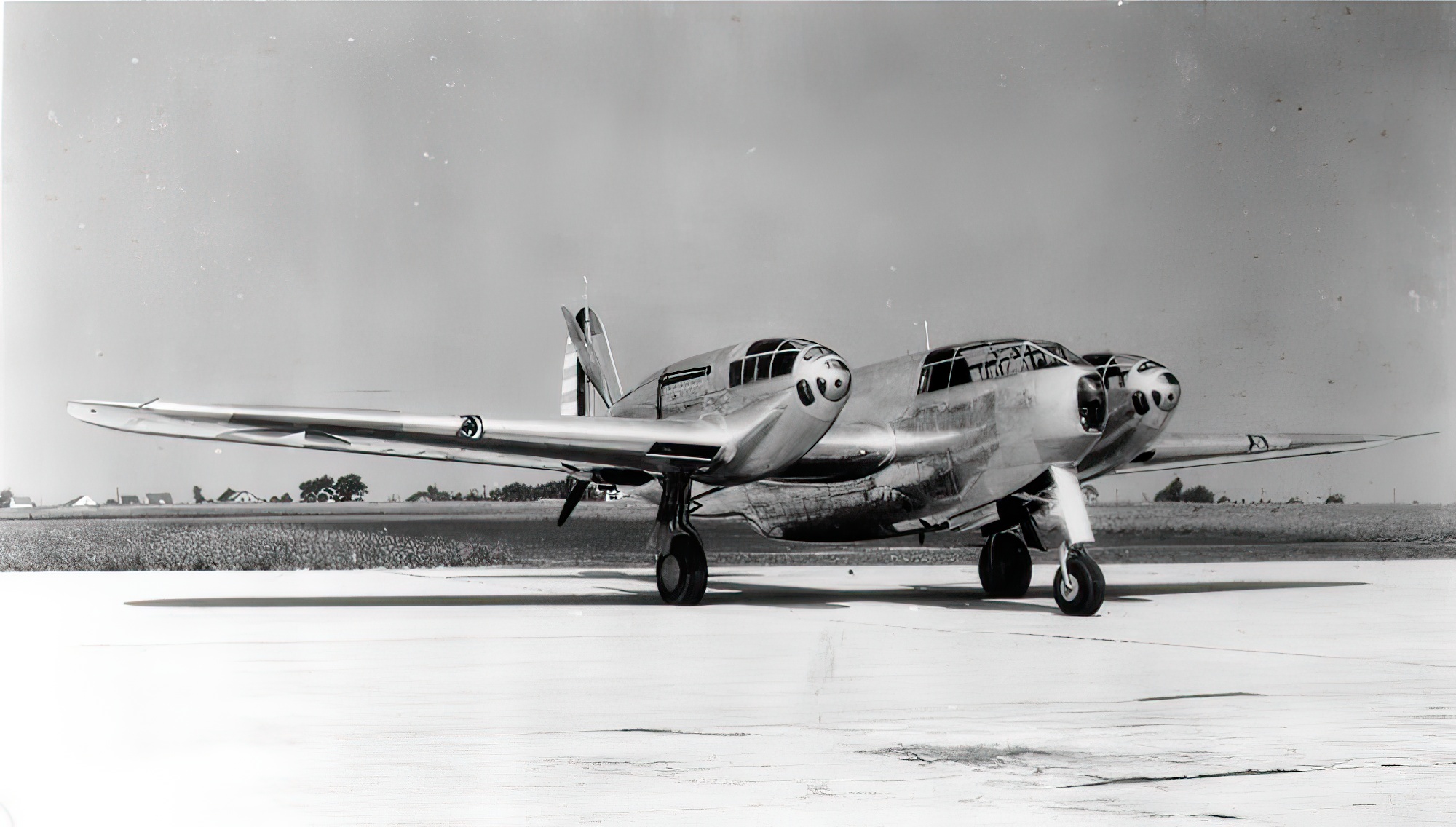

The Airacuda had a very sleek and even “futuristic” design, compared to most American aircraft that were in service at the time of the YFM-1’s maiden flight on September 1, 1937. It was powered by two 1,150-hp Allison V-1710-13 12-cylinder liquid-cooled engines driving three-blade propellers arranged in a pusher configuration. The production airframes were equipped with slightly different version of the Allison V-1710 power plant, the V-1710-23 and 1710-41.

Seating the crew

Advertised as a “mobile anti-aircraft platform” and “the most deadly thing in the sky,” the YFM-1, where FM stood for “fighter, multiplace,” carried a whole battery of guns. To operate them it had an unusually large for a fighter crew of five. With the pusher propeller facing backward, the fore part of each engine nacelle hosted a Madsen 1.46in M4 cannon. In an arrangement unique to the Airacuda, the nacelles also hosted gunner compartments. However, these gunners were not supposed to fire the cannons, which were normally operated by a fire control officer sitting inside the fuselage.

While the gunners sitting inside the nacelles could, if necessary, aim the guns as well, their key task was simply to reload the cannons with ammunition. Given that the cannons were loaded with magazines containing only five rounds each, there was quite a lot of work for them to do. So, it would probably be more accurate to call them loaders, rather than gunners.

The other Airacuda crew members included the pilot, the copilot, who was also the navigator and fire-control officer, and the radio operator sitting in the mid-fuselage, who also fired two browning machine guns from the side blisters in the event of an attack from the rear. The fire-control officer also had at his disposal a periscope under the aircraft’s nose to check for enemy fighters approaching from behind and below.

Counting the problems

Like many bold, unconventional designs, the Airacuda was plagued by numerous problems. There was, in fact, a very long list of issues:

- With a top speed of 244 mph, it was slower than many bombers—not particularly good for a would-be bomber hunter.

- The M4 cannons had a low muzzle velocity and tended to fill the nacelle compartments with toxic smoke.

- The plane could carry only 600lb of bombload, which meant it would not be of much use in the ground-attack-role either.

- The engines often overheated both on the ground and in the air, because pusher propeller provided no propwash to cool them. In fact, on-the-ground overheating was so much of a problem that the Airacuda had to be taxied by a special vehicle. And only once it was on the runway and ready to take off, did the pilots start its engines.

- Flying the Airacuda on just one engine was practically impossible—if one of the engines failed, the aircraft immediately went into a spin.

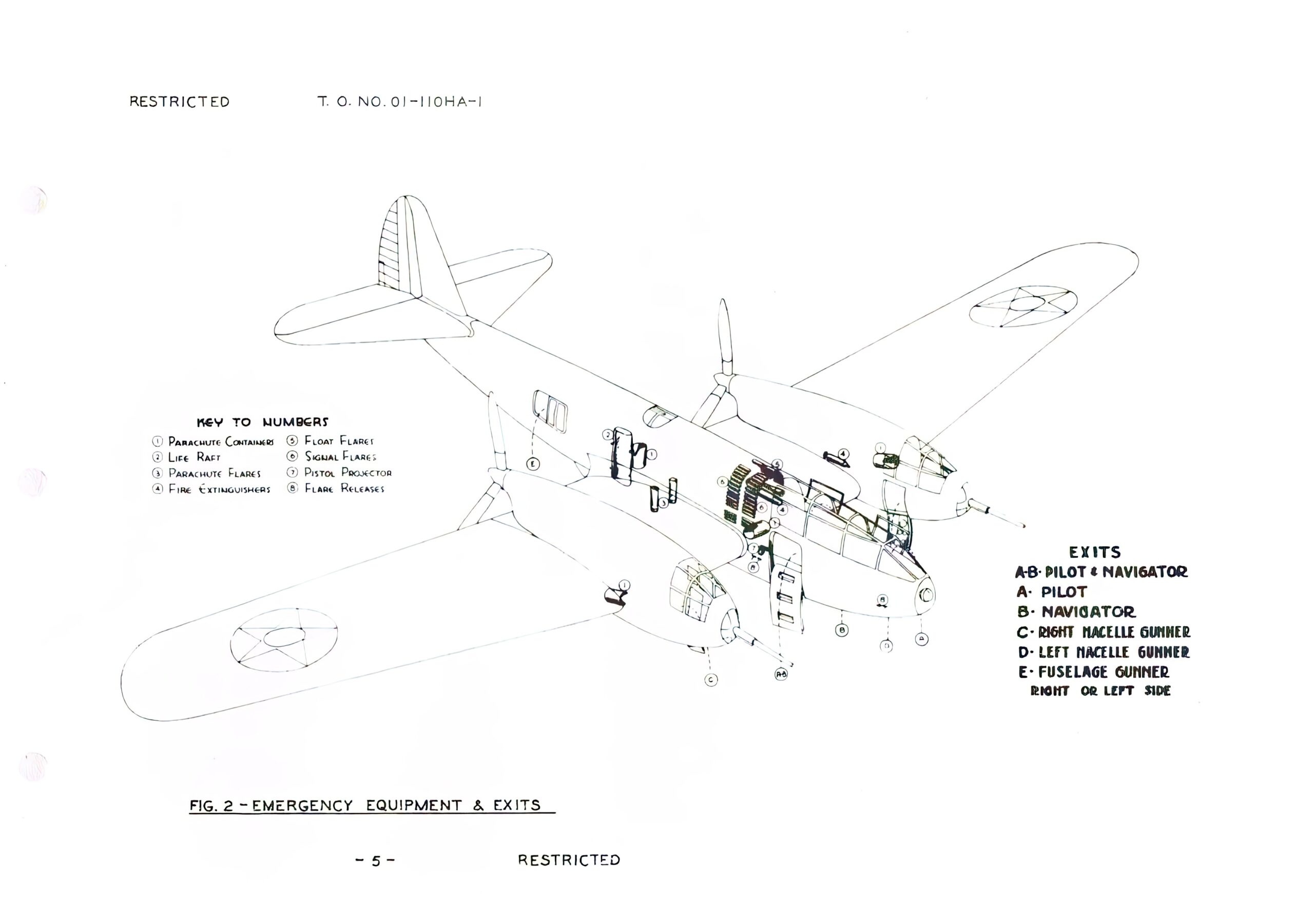

- Bailing out was problematic for all crewmembers, especially for the nacelle gunners. They risked being struck by the propellers behind them, so before they left the aircraft the propellers had to be feathered and brought to a standstill. An additional arrangement using explosive bolts was later made so that the gunners could simply jettison the propellers in an emergency.

- The aircraft’s complex electrical system relied solely on a full-time auxiliary petrol motor running in the fuselage. Whenever that motor failed, the pilot lost control over flaps, gear, fuel pumps, and engines.

Facing the stark reality

All these problems were pretty evident in the prototype. Still, Bell got the go-ahead for a production run and manufactured a dozen aircraft between 1938 and 1940. These equipped one squadron of the United States Army Air Corps (USAAC). However, actually flying them was a very difficult and uncertain business unpopular among pilots. Maintenance was always a problem, too. Hence, the Airacudas spent most of their time grounded, earning the nickname of “hangar queens.”

Only two airframes were lost and one man killed in accidents involving the Airacuda, but given the small number of the aircraft produced, even that was a worrying number. Generally, the ratio of various accidents and incidents to the number of flying hours was too high. So, the production soon ceased and the Airacudas already in service were phased out by early 1942.